“The Way“ by Lennart Brede featuring Yaneq

“The Way” – A visual manifesto beyond narrative, and it’s no coincidence that the film shares the title of Yaneq’s song.

“Erich, it’s over. You have to go.“

There is still a storyline somewhere. But often it feels like a collage. Contrary to the concept of visual narratives, where an idea is planted at the beginning of a film and later harvested within the story. In “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” (1949), Joseph Campbell describes how myths and stories from all cultures follow a shared narrative structure: the typical “hero’s journey” has three phases: “departure” – the hero leaves their familiar world for adventure, followed by the “initiation” – where they experience trials, encounter allies and enemies, undergo transformation, and finally the “return” – the hero comes back changed, bringing treasure, knowledge, or healing to the world. This structure can be sensed faintly, but Brede deliberately avoids a clear dramatic arc and a clearly defined protagonist/antagonist structure.

The short film is not a traditional movie. It is a visually rich collage – a political, spiritual, aesthetic trip that consciously resists clear interpretation. No classic beginning, no defined narrative. Instead: fragments, symbols, dream-like scenes. A deliberate break with the expectation that a story should guide us, explain things, and release us in the end. That someone narrates, defines, dictates our story.

Here is a protagonist who acts, experiences, is redeemed – but no resolution is given. And the viewer? They're not satisfied, instinctively trained in what a story is supposed to be – a kind of prescribed rule on how a story must function.

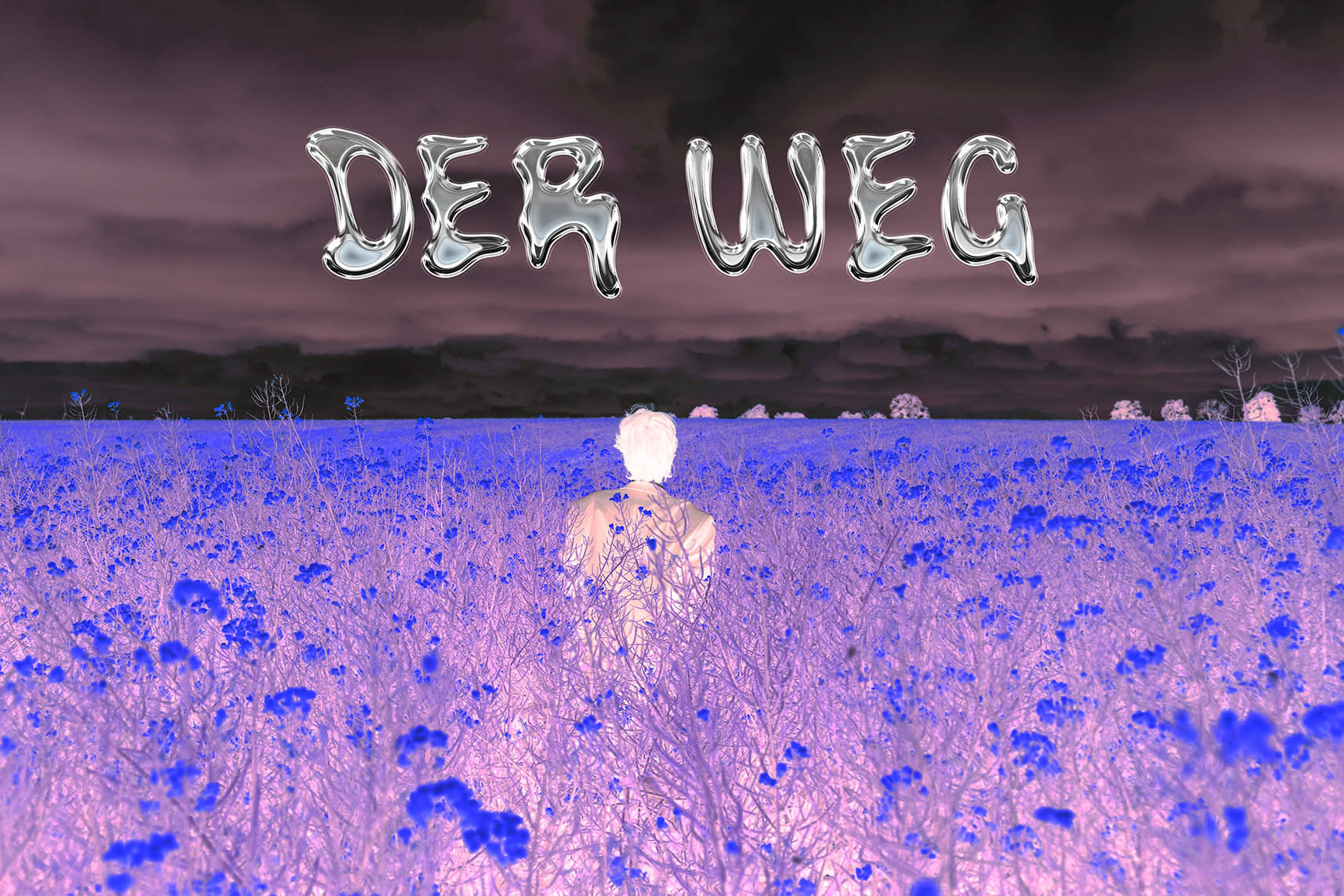

What is even happening? The main character – a young woman – does not speak. Is she running away or toward something? From herself? To find herself? Both.

She acts, suffers, runs, is led, seduced, touched, anointed, transformed – and yet remains permeable. She is not a heroine in the traditional sense, more a vessel. A projection surface. A seeker. Or a medium – through which collective fears, hopes, stories, and traumas articulate themselves. Her voice is silent, but the film screams. Right at the start: a moment of catharsis – screaming, vomiting. And it doesn’t matter why. This emotional climax marks not the end, but the beginning of the journey.

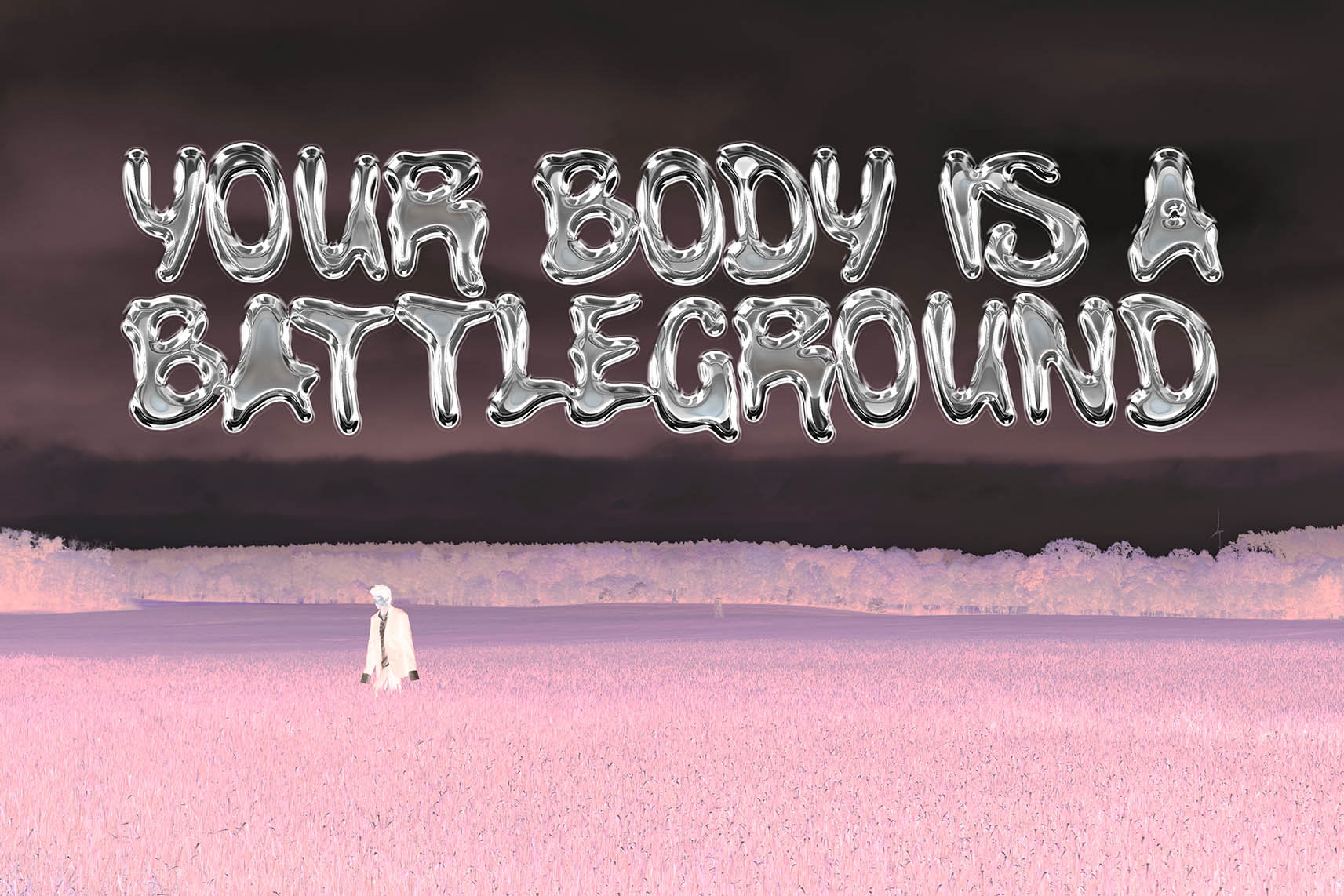

What follows are images, quotes, and associations: religious references: Mary, Last Supper, Anointing; political allegories: Honecker, Stasi, crystal meth in the Stasi, Nazi bunker; cultural reflections: Barbara Kruger, Ton Steine Scherben, Spring Breakers, Ku Klux Klan, the Spanish Day of the Dead in Catholic tradition. The parrot – sarcastic devil or oracle – says to her: “Your body is a battleground.” More than a quote. It is a statement. The body becomes a cathedral, a place of contention with power, control, desire, and resistance.

At first, one assumes the wandering, silent woman is at the center of the narrative. But the supposedly subordinate woman who re-dresses her in the bunker wears the crown – she is the Mother of Gates, holding the power and influence to affect Maryam’s (the Arabic form of Mary) rise. The wise queen opens the gate – and with it, hope for solidarity and equality in a world full of gatekeepers.

Codename: Maintenance Unit 12 – The camera moves through surreal spaces – a nuclear bomb-proof bunker – “Harnekop” – becomes a mythological site. “The Harnekop bunker was the ‘main command center in the event of war’ of the ‘Ministry of National Defense of the GDR.’ The bunker is a three-story protective structure of protection class A. With a footprint of approx. 63 × 40 m and more than 7,000 m² of usable space, it is one of the largest bunkers in the former GDR. In ‘deployment,’ it could have provided shelter to 500 military personnel (command and support staff) for a maximum of 4 weeks.“

Inside the bunker: a Honecker portrait, next to it one of Willi Stoph, high-ranking official of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), who held numerous key positions in the GDR government. His style and influence were considered pragmatic and reliable by Western analysts – not a fanatic, but a loyal administrator of the SED course. He operated long in the shadow of powerful figures like Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker. On October 18, 1989, he coined the decisive sentence in the SED Politburo: “Erich, it’s over. You have to go.” – thereby initiating Honecker’s resignation. On November 7, 1989, he resigned along with the entire government, was expelled from the SED a few days later, and later imprisoned.

In front of that: a man boxing, fighting his own values. Next to him: a child boxing – the next generation, striking more precisely than him, working through supposed ideals.

In the washing scene, the protagonists appear as soldiers, perpetrators, priests, companions. All characters are dark and brutal, and then – no longer opposed to Maryam – they assist her. Initially hostile, then helpful. Everything keeps shifting. What was still true? What is political, spiritual, exaggerated? The answer remains absent – and that is the point. “The Way” is a kind of anti-narrative ritual. Not explained, guided, returned safely – but challenged.

Just like performance artists Ulay & Abramović – they too disoriented their audience, breaking things open, pushing us. A narrative without explanation. Not a moral tale, not commentary, but an invitation to reflect on our own images, stories, and conflicts. The film denies interpretive authority. Instead: an open field. A community of seekers, uniting at the end. The protagonist arrives alone – but departs with others. The utopia: nature, community, solidarity. Children in masks walk with her into the future. The past was dark, monitored, poisoned – but maybe the way out is also the way toward something better. Maybe. If we dare not to understand the film – or ourselves – immediately, but simply to begin.

Text by Judith Plodeck